What if you took all of the elements of a building, hacked them apart and put them back together again without apparent rhyme or reason? That’s basically the visual effect of Deconstructivism, a school of architecture that explores fragmentation and distorts the walls, roof, interior volumes and envelope of a building in a sort of controlled chaos, sometimes to intentionally create discomfort and confusion.

“We don’t want architecture to exclude everything that is disquieting,” the co-founders of Austrian architecture firm Coop Himmelb(l)au wrote of their aesthetics, essentially defining the postmodern architectural movement that has defied conventions and courted controversy since the 1980′s. The following seven structures, from five architecture firms that were celebrated at the Museum of Modern Art’s 1988 Deconstructivist Architecture exhibition, are among the most provocative structures in the world.

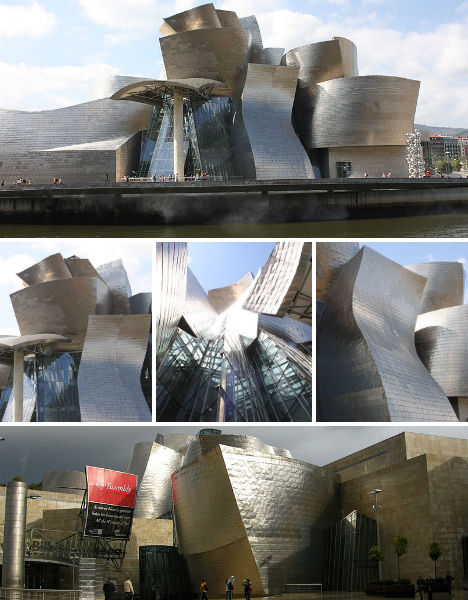

Frank Gehry’s Bilbao Museum Guggenheim, Spain

(images via: wikimedia commons)

When you think ‘deconstructivist’, what’s the first building that pops into your mind? If you’re at all familiar with the term (and not a student of architecture), it’s probably Frank Gehry’s iconic and unforgettable Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain. In 1978, Gehry took the steps that would bring him to this point, drastically changinghis own standard, somewhat boring suburban Santa Monica house into the groundwork for an entire architectural movement. He literally deconstructed the house, ripping out sections and reassembling them into an eccentric fusion of traditional and modern aesthetics. By the time he got to the Guggenheim, completed in 1997, Gehry had perfected a shocking new style that dazzled critics and the public alike, although many in the architectural community may disagree on such points as creativity versus functionality.

While Gehry himself shirks the Deconstructivist label, his work – particularly the Guggenheim – has been strongly associated with the architectural style that has been carried forth by a number of other architects around the world. Luminous and shape-shifting, the Guggenheim is hard to pin down, seeming almost to undulate in the sunlight and the dappled reflection of the Nervion River upon which it sits. The wildly original design, as well as construction of the building, was aided to a large degree by the use of Computer Aided Three Dimensional Interactive Application (CATIA). The many organic volumes that make up the whole are covered in titanium panels that resemble fish scales, a tribute to the museum’s location.

Coop Himmelb(l)au’s UFA-Cinema Center, Dresden, Germany

(images via: architizer)

The Austrian firm Coop Himmelb(l)au, which now has offices in Los Angeles and Guadalajara as well as Vienna, is often credited with producing the first realizations of Deconstructivist architecture in Europe. The cooperative’s rooftop law office extension in their home city raised eyebrows when it was erected in 1988 with its parasitic appearance, and its Funder factory building in St. Veit Glan, Austria was certainly eye-catching. In 1998, Coop Himmelb(l)au completed the UFA-Cinema Center in Dresden, Germany, which consists of two volumes: the ‘Crystal’, a massive glass lobby and public square that seems to lean precariously to one side, and the ‘Cinema Block’, which holds eight cinemas with seating for 2600. The firm says that with the UFA-Cinema Center, it aimed to “confront the issue of public space”, saying “By disintegrating the monofunctionality of these structures and adding urban functions to them, a new urbanity can arise in the city.”

Independent of Gehry’s influence, Coop Himmelb(l)au and other international architects who produced important Deconstructivist works were inspired by movements in modern art such as Cubismand Dada, and Russian avant garde architecture of the 1920s.

Peter Eisenman’s Wexner Center for the Arts, Ohio

(images via: wikimedia commons)

New Jersey-based architect Peter Eisenman designed the first major public Deconstructivist building in America, the 1989 Wexner Center for the Arts at Ohio State University. The Wexner Center was something of an experiment in Deconstructivism; it’s certainly not a blank, passive space for the display of art but meant to be a dynamic work of art within itself. It’s a five-story, open-air structure featuring a prominent white gridwork that resembles scaffolding in order to appear intentionally incomplete, in a permanent state of limbo. These very design ideas have caused significant controversy because, in some cases, they interfere with the function of the building, such as fine art exhibition spaces where direct sunlight could potentially damage sensitive works of art. Furthermore, the center has no recognizable entry, with most of the sculptural ornamentation on the sides where no doors exist. The interior spaces are no less eccentric; some visitors even report feeling nauseas because of the ‘colliding planes’ of the design.

Controversial though it may be, Eisenman’s Wexner Center remains among the most important examples of Deconstructivism, bringing abstract ideas and theories to the fore and perhaps elevating them above purpose and practicality.

Bernard Tschumi’s Parc de la Villette, Paris, France

(images via: laurenmanning, mo_cosmo, als0lily)

The Parc de la Villette in Paris is unlike any public park you’ve ever seen, with its strange network of bright red structures designed, according to architect Bernard Tschumi, not for ordered relaxation and self-indulgence but interactivity and exploration. Built from 1984 to 1987 on the grounds of a former meat market, the park contains themed gardens, playgrounds for children, facilities dedicated to science and music and 35 architectural follies, all of which are inspired by the ideas of Deconstructivism. Visually and intellectually stimulating, the steel follies provide a frame for activity, in contrast to the idea of a park as open green space.

In his book ‘Architecture and Disjunction’, Tschumi describes meeting the French philosopher Jacques Derrida to talk about Derrida’s concept of deconstruction, which Tschumi and Eisenman have pulled into their own architectural aesthetics. “When I first met Jacques Derrida, in order to convince him to confront his own work with architecture, he asked me, ‘But how could an architect be interested in deconstruction? After all, deconstruction is antiform, anti-hierarchy, anti-structure, the opposite of all that architecture stands for’. ‘Precisely for this reason,’ I replied!”

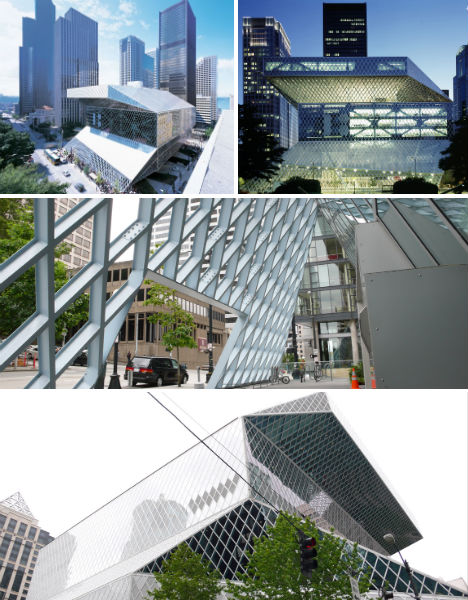

OMA/Rem Koolhaas’ Seattle Central Library, Washington

(images via: archdaily)

With famed architect Rem Koolhaas at the helm, architecture firmsOMA and LMN gave Seattle one of the world’s most stunning Deconstructivist buildings in the form of the Seattle Central Library. This groundbreaking structure consists of eight horizontal layers in varied sizes, encased within a structural steel and glass skin which defines additional exterior public spaces. Elevating the library beyond a mere receptacle for books, the design focuses on information as a whole where all forms of media can be accessed, reflected upon and discussed.

Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas, a founding partner of OMA, has largely defied labels, variously categorized as Deconstructivist, Modernist and Humanist by critics. The Pritzker Prize winner may at times be controversial for designs that seem visually disjointed or difficult to actually use, but in the Seattle Central Library he has helped create one of America’s most notable structures, and one of the most important Deconstructivist buildings in the world.

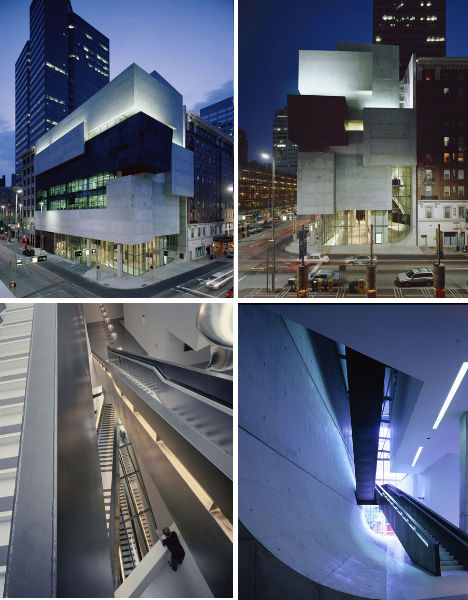

Zaha Hadid’s Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, Ohio

(images via: zaha-hadid.com)

Baghdad-born, Britain-based Zaha Hadid, the first woman to win a Pritzker Prize, has also contributed a number of notable Deconstructivist works to international architecture. One such structure, Hadid’s first design to ever be built, is the 2003 Lois and Richard Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art in Cincinnati, Ohio. Known popularly as the Contemporary Arts Center (CAC), the building is both blocky and soft, defined by geometric volumes on the facade and featuring an unusual ‘urban carpet’, with the ground slowly curving upward from the sidewalk outside into the building and ultimately up the back wall. A ramp resembling a twisted spine draws visitors up to a landing at the entrance to the galleries.

Daniel Libeskind’s Jewish Museum, Berlin, Germany

(images via: daniel-libeskind.com)

Is Daniel Libeskind’s Jewish Museum in Berlin the best example of Deconstructivism in the world? This zig-zagging structure, clad in thin zinc sheeting punctuated by windows in shapes meant to recall wounds and scars, houses two millennia of German Jewish history. It sits upon a space once occupied by the Berlin Wall, and butts up to an 18th century appeals court which is also part of the museum. Its shape is said to be inspired by a warped Star of David, and its jaggedness is likened to the human condition. A huge void cuts through the form of the museum, symbolizing the absence left by the thousands of Berliners who were killed or deported in the Holocaust.

Says the architect, “I believe that this project joins architecture to questions that are now relevant to all humanity. To this end, I have sought to create a new Architecture for a time which would reflect an understanding of history, a new understanding of Museums and a new realization of the relationship between program and architectural space. Therefore this Museum is not only a response to a particular program, but an emblem of Hope.”

"The speed of everything is quite frightening," said Alistair Hicks, an art adviser and curator for Deutsche Bank.

"The speed of everything is quite frightening," said Alistair Hicks, an art adviser and curator for Deutsche Bank.